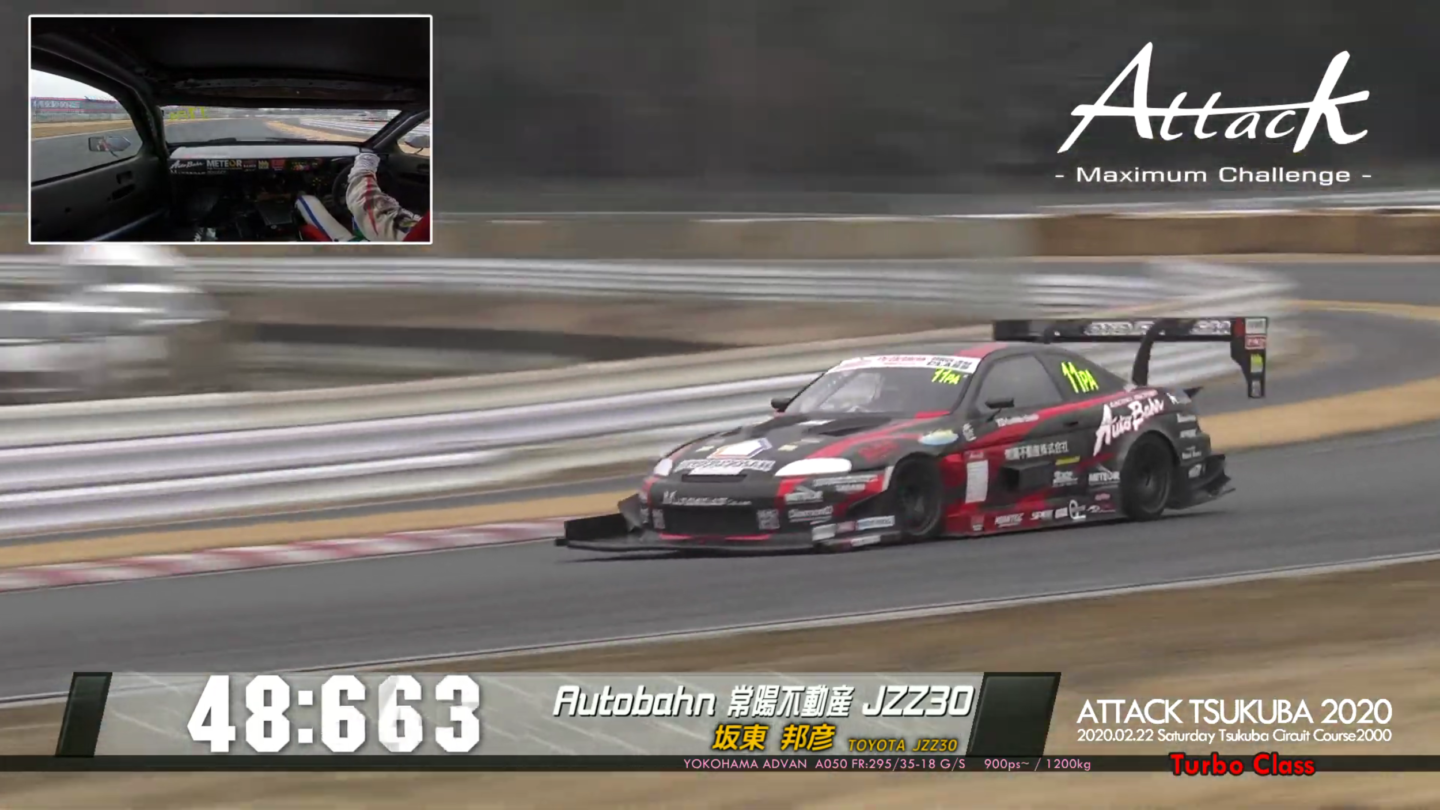

This isn’t the first time Kunihiko Bando’s outrageous creation has been featured here, but this footage is one which helps highlight how this man’s driving has adapted to suit his steed. His 2JZ-GTE-powered Toyota Soarer, also known as the Lexus SC300 in the U.S., has more versatility than one might imagine a grand tourer would. The Soarer’s weight, long overhangs, and intimidating horsepower seem like they would reduce the GT’s chances of a competitive time around a technical track like Tsukuba Circuit, but Bando and Racing Factory AutoBahn addressed these potential shortcomings in several ways.

A Misplaced Drag Car

Firstly, he trimmed the heft of the heavyweight. A twelve-year diet has trimmed the weight of the vehicle all the way down to a respectable 2,590 pounds, thanks in large part to SightHound’s carbon panels and Lexan windows.

A custom 3.1-liter 2JZ-GTE, filled with HKS pistons, Carrillo rods, and a factory crankshaft, is force-fed by a Garrett G42-1450 turbo. That snail spits its pressurized air through a Hypertune intake manifold and a Bosch throttle body. When fed with E85, it sends up to 1,200 horsepower through a paddle-shifted Albins ST6 sequential gearbox to the 295 section Yokohama Advan A050 tires, which do a fantastic job considering the circumstances. Simply put, an FR with this much power should be useless here.

Suited to Straights

Tsukuba Circuit’s slow corners, combined with the car’s less-than-ideal weight distribution and violent power delivery means Bando has to use a few tricks if he wants to do more than lay long, black stripes on the track. Compared to earlier footage full of oversteery moments, Bando’s done something in these runs to settle the rear of the car on acceleration. The tire size has remained the same, and the aero probably isn’t too effective in these slow corners, so those items can be ruled out. Upon closer inspection, his lines look a lot different.

Watch the way he doesn’t even try to use the full width of the road leaving Turns 5 and 11 (0:37 and 0:54 above, respectively). There, he seems to overslow the car mid-corner and square the line, which allows him to straighten the car earlier than most would. He’s prioritizing the exit.

It might not look the fastest, but this has made a huge improvement in lap times. Notice how little steering correction is needed at corner exit compared to an earlier Tsukuba attempt seen here. Even if this approach reduces his apex speeds considerably, straightening the car sooner helps him leave the corner with less wheelspin, which lengthens the straightaways by playing to its greatest strength: its incredible power.

An onboard from an even faster lap:

Actually, this motor has been detuned slightly for this particular run. Though it’s capable of producing 1,200 horsepower for faster tracks like Twin Ring Motegi, this Tsukuba run is using just 900—and some fifty horsepower down from an earlier attempt there.

There are some sections where he’s still traction limited, but since speeds are higher and it makes sense to try and use the full width of the road. Notice how he gets the rear to rotate as he brakes into Turn 5 under the Dunlop Bridge—any more and he’d be countersteering into the corner. But by throwing the car in with the nose weighted, he gets the Soarer straightened so as to minimize wheelspin at the exit.

A strange mix of absurdity and circumspection is needed to build and drive a car this wild on such small tracks, but Bando’s managed to find the proper combination and continues to whittle his times down. He’s a little behind the 4WD competitors, but this car was never really designed to race road courses. His 52-second laps at Tsukuba are a testament to how Bando’s been able to emphasize the strengths of a boxer with the agility of a gymnast.