Imagine something with the girth and build ethos of a NASCAR, but a little leaner, a little nimbler, and generally a little more athletic. While not as focused or incisive as a modern GT car, the Trans Am TA2 is something quite special, since it combines some of the appealing qualities of modern racers with old-school handling characteristics.

The Trans Am TA2 isn’t something that relies on aerodynamic grip, and uses big tires to put a lot of power to the pavement. It’s fairly light for something based loosely off a stock car: the TA2 is a tube-framed machine—no carbon tub business here—with a fiberglass body, and all that adds up to about 2,800 pounds. As light as it is, it’s limited somewhat by the lack of downforce, the tire technology, and the size of the brakes (rotors have a maximum diameter of 12.19″). Therefore, the capable driver knows how to balance the brutality brought by the snarling V8 and the limitations of the platform.

Without active suspension, traction control, or ABS, Trans Am cars are still very violent and require a specific touch. The lack of driver aids, lots of horsepower, and low downforce is the recipe for making the cars exciting to watch, and by the looks of the onboard video here, quite demanding to drive. Plus, the competition in the TA2 category is fierce thanks to mechanical parity; brakes, wheels, and shocks are strictly cost-capped. The components aren’t supposed to be space-age either; no titanium or carbon fiber components are allowed other than the driver’s seat. Low cost caps are implemented to ensure an accessible, competitive field, and a driver can obtain a competitive car for less than ninety grand. Not exactly peanuts, but for the performance on offer, it’s a bargain.

Though Trans Am cars have historically used bias-ply tires, the TA2 Mustang seen here employs hybrid tires from Pirelli, and they’re tricky to manage. These don’t perform quite like a radial, and as driver Thomas Merrill notes, “The tire doesn’t roll and take a set. You feel like you’re riding on top of the tire.”

These tires don’t give quite the feel and the loading that you’d want in a modern car, but that adds to the challenge of mastering the machine. The car has to be treated with a special touch, since it’s easy to overwhelm the brakes and tires, but in exchange, they’re pretty sturdy. “In fact,” Merrill describes, “in many ways the Trans Am cars are tougher [than GT3 cars] and can handle more abuse over curbs than some modern cars. You can get greedy with touching other cars without damaging your car.”

Getting the most of the tire takes a delicate touch; they’re not the stickiest in the business. However, they’re good at curb hopping and trading paint. In this photo, the smaller Australian-spec wings are shown.

Limited by the tire technology, the quick driver knows a Trans Am car’s excess of power relative to grip. The Ilmor engine, with the TA2-class intake restrictor in place, the engine makes 480 horsepower at 6,800 rpm, and it’s enough to spin the rears just about anywhere at Sonoma Raceway. Therefore, Merrill’s frequently hanging the rear end out, and rarely can he go flat to the floor with any sort of lateral loading; the throttle is depressed with plenty of caution. The gears are widely spaced, and the transmission allows for clutchless upshifts and downshifts. That means Merrill blips with the right foot and brakes with the left, which takes some discipline.

Braking and Downshifting

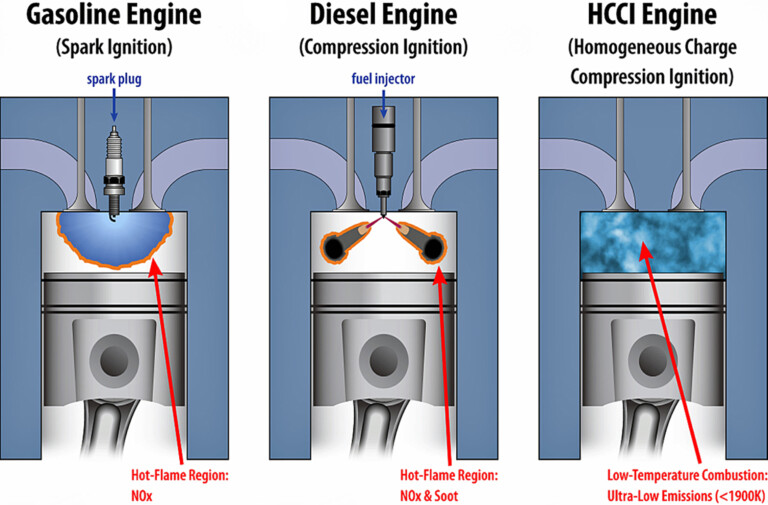

Merrill’s biggest challenge with the Trans Am monster isn’t with harnessing the motor—it’s finding the right rhythm when downshifting. Because the Ilmor motor, based off a 351 Windsor, displaces 371 CI and has a 10.8:1 compression, it’s happy to lock the rear wheels with engine braking. Therefore, the quickest guys in Trans Am cars know not to rush the downshifting phase of the braking zone and give the appropriate amount of time between gears. As Merrill demonstrates, he never rushes through the gearbox, because wheelhop “bounces the rear end in the brake zone, which makes the car unstable on entry and can hurt braking performance.”

The braking phase is tricky for another reason, and, strangely, a little like that of a Formula Ford. Those cars, which run relatively small brakes and tires and have little aerodynamic grip (excluding winged Formula Ford 2000s and the like). To keep the platform balanced in the braking zone, both the Trans Am and the Formula Ford reward a softer initial application of the binders.

As Merrill notes, “[The Mustang] likes to take a set with all four tires in the brake zone, rather than slamming down on the nose like most modern cars.” Though the TA2 Mustang might look a little like a modern GT3-style car, you can’t violently stomp on the middle pedal at the beginning of the braking zone. If the platform is settled on the way into the braking zone, “It will handle quite a bit of pressure if it’s applied correctly,” notes Merrill, “so, you can brake harder than a Formula Ford, but you get to your maximum pressure in a similar way.”

Diving at the front—it’s important to let the car take a set in the braking zones. Photo credit: Trans Am

Making it Last

At 2,800 pounds, the cars aren’t too heavy for something related to a stock car, but it’s not a featherweight by any means. The brake pads are something that can fade over the course of a race, and Merrill is still experimenting with pad compounds for a longer lifespan. Getting strong braking performance throughout the whole race is crucial; resource maximization is of prime concern with the Trans Am car.

Mid-Corner and Exit

After a tidy entry to the corner, Merrill rolls off the brakes and focuses on rolling plenty of speed, off-throttle, through the middle of the corner. The way the differentials work in these cars, they don’t respond well to lots of throttle for stabilization mid-corner. The Gleason differential and the rear end does, however, do a decent job of putting the power down.

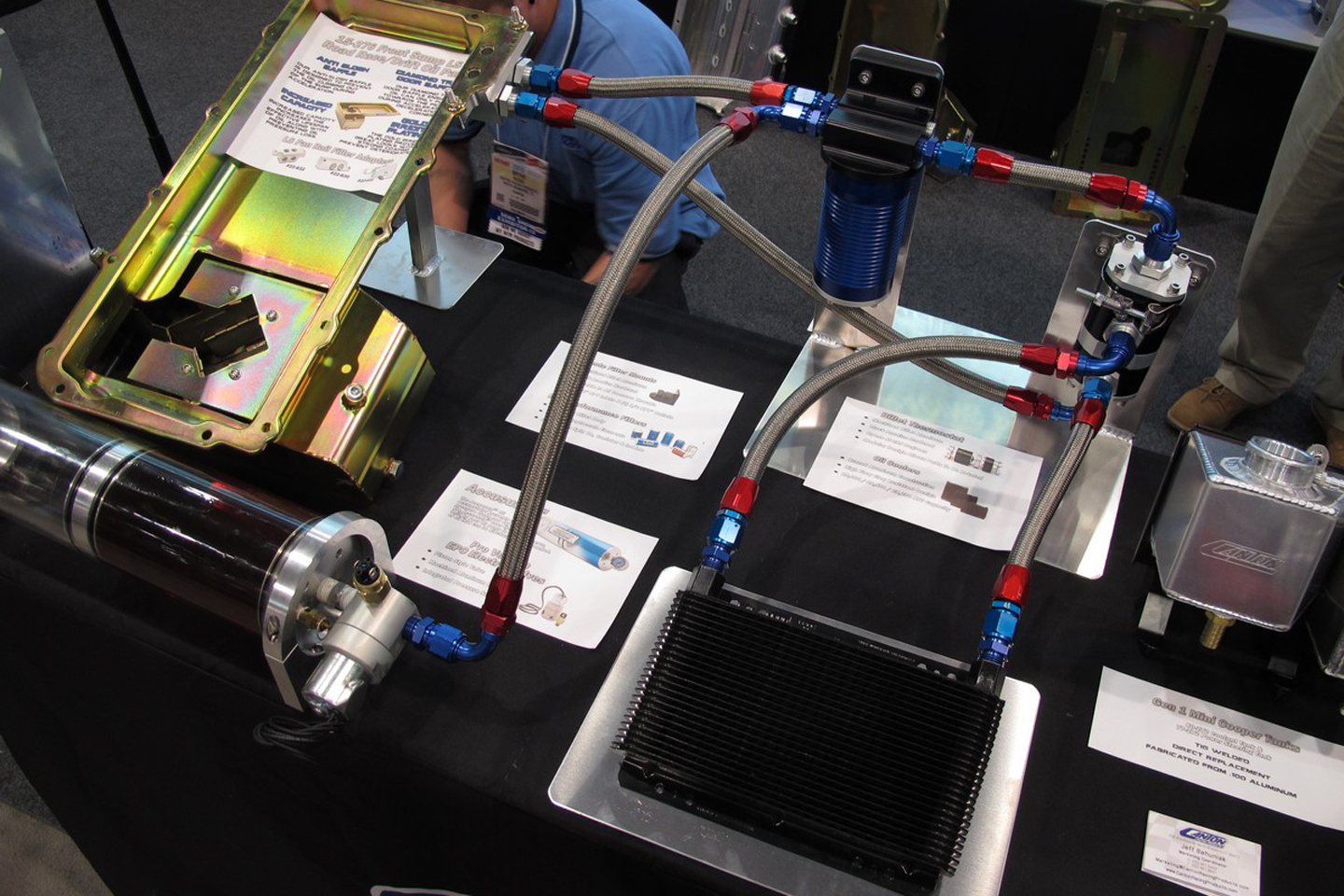

The solid rear axle isn’t thought of as the ideal setup for a road racing car, but the chassis providers (Howe Racing, Mike Cope Racing, M-1 Motorsports, and Meissen Engineering) figured out how to make good use of the grunt. The standard three-link rear end is made up of a reliable Tiger quick change, equipped with an integral cooling pump with an external cooler.

This means the corner-exit phase is defined by wheelspin and oversteer. Thankfully, you can get away with a bit of slip angle when putting the power down, but rarely does the rear tire accept all the grunt, not even in the quickest corners. The slithering cars aren’t dull for the observer, but the successful driver knows how to tread the line between showmanship and conserving tire life. In fact, more so than the brakes, the rear tires are the limiting factor.

Some degradation from wheelspin is inevitable—just look at the way Merrill has to wrangle the Mustang at corner exit, and even through the high-speed Turn 10! It shouldn’t be torque limited there, but it is! Therefore, he has to compromise a little slip angle with tire preservation.

As is often the case with big, powerful cars like these, success in Trans Am comes as the result of resource management. Like racing a stock car, the driver needs to keep their pace up without hammering their machinery heartlessly; it’s very important to get the setup right, since that allows for strong performance over the entire race distance. The key to racing a Trans Am car, Merrill states, “is trying not to use 100% of the car’s performance early so that it can be maximized later in the race.”

Though these sturdy cars can take trips over curbs or through the grass, they can burn through tires if the drivers aren’t careful. Photo credit: Trans Am

“Within the first few laps, you’ll know what end of the car needs to be conserved for the end, because inevitably the setup will favor one end over the other,” says Merrill. If the setup is just right, the car can take more abuse. “A driver can be fairly aggressive with the car if tire wear and braking force is split evenly among all four corners.” Seeing as the video above was of Merrill’s break-in session with the car, there’s still quite a lot of performance left—which is hard to believe. Balancing the act of manhandling with some mechanical sympathy, Merrill put on a masterclass for those looking to get into one of the most competitive Pro-Am series in America.

__________________________________________________________________

Thomas Merrill works primarily as a racing coach at the club to semi-pro levels, and offers tutelage for anyone wanting to improve their ability in sports cars, stock cars, and formula cars. Other times, he works as a development driver for major manufacturers and a few notable racing school, and for those looking to improve their craft, his information can be found here.